JOHN BAEDER

His Remarkable Life and Art

by MB Abram

Part I

In collaboration with ACA Galleries in New York, MB Abram is honored to present master works by John Baeder including oil and acrylic paintings, watercolors, prints, photographs and sculpture. This is the first presentation of a three-part online exhibition.

It's fitting that Baeder’s work is presented in partnership with ACA Galleries. Established in 1932 at a time when there were few American galleries showing contemporary art, ACA has maintained a leadership role in showing important American and international artists in nearly 90 years since.

Recently ACA exhibited the work of Faith Ringgold at Frieze London. That exhibition like this current one was presented online due to Covid-19 restrictions. It is natural that Baeder’s work is in the company of other artists historically exhibited by ACA such as Faith Ringgold, Alice Neel, Charles White, and others. Baeder’s work also shares the passion of June Wayne and Jan Haag, with whom MB Abram has long been associated.

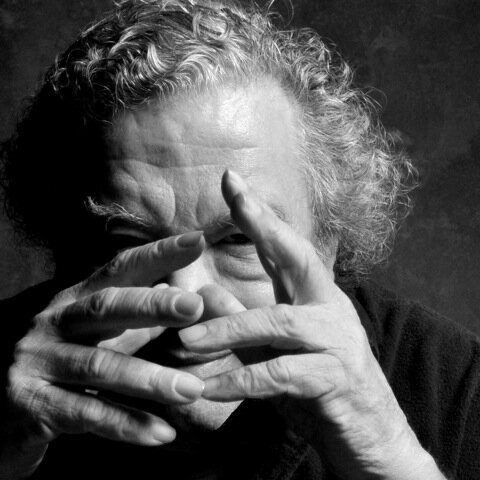

For the last three years Baeder has been struggling with failing eyesight due to advanced macular degeneration. He is now unable to paint. Works presented here, from his personal collection, are the last that will be available from the collection and represent a special opportunity for the serious collector. A number of these works are being made available for the first time.

John Baeder photographed by Richard J.S. Gutman. Original slide now in the Richard J.S. Gutman Diner Collection at The Henry Ford.

“My First Aim Is Not That I Be An Artist, But That I Be A Fully Realized Human Being. First And Foremost That is What Is Important.”

The Beginning

Baeder was born in South Bend, Indiana on December 24, 1938. His family moved to Atlanta, GA when he was a year and a half. While quick to make friends in Atlanta, Baeder had interests quite different than his classmates, and often at odds with his practical parents. At age twelve, he became fascinated with collecting. But instead of the baseball and sports cards that intrigued some of his peers, Baeder was drawn to aircraft. He spent hours scouring magazines devoted to airplanes, absorbed in the mechanical and sculptural details of these flying machines.

Traveling by train as a young boy to visit his mother's family in South Bend, Indiana, Baeder would stare out of the windows at the passing landscapes. Later he would remember these views as pictures, framed by the window's edges. He loved the trains’ diner cars, a center of activity and hospitality, exotic to his child’s eyes. These memories, and others, would later be reflected in his works as an artist.

At a time and a place when his contemporaries were aspiring to more traditional careers, Baeder had recognized a different path for himself. By age fifteen, he was attending live drawing classes at the then small High Museum in Atlanta. At sixteen, Baeder expressed a desire to his parents to attend the Royal College of Art in London. This destination was outside the family means or understanding, but at seventeen Baeder found a local alternative: the art department at Auburn University which had acquired a reputation for its progressive approach.

Traveling between Georgia and Alabama had a profound effect on Baeder. There was no interstate at the time, and driving along Highway 29 and the rural backroads, Baeder was exposed to roadside culture, which he saw as embodying something uniquely American, and for which he developed a lifelong passion.

Photograph from Baeder’s first art exhibit, Judith Alexander Gallery, Atlanta, GA 1964

Flight

Returning at age twenty-one to Atlanta after four intense years honing his artistic talents at Auburn, Baeder was hired as an art director on the first showing of his portfolio by The Marschalk Company, parent company of advertising powerhouse McCann-Erickson. He worked on large campaigns, including Fanta, Sprite, and Tab, these brands of Atlanta based Coca-Cola Company and Baeder’s talents in the Atlanta advertising market were quickly recognized. He was soon offered a transfer to the New York offices of The Marschalk Company. There he became a superstar art director, this at a time when the industry was at the apex of the fast-paced life, depicted in such popular television series as Mad Men. Despite his success an art director, Baeder’s heart was elsewhere, in a personal artistry.

Baeder’s travels on Route 29 between Auburn and Atlanta had caused Baeder to view the landscape and its gas stations, motels, and eateries in a new way, sensing they were imbued with an anima reflecting the people and ethos of America. He was haunted by the quickly changing, and soon disappearing roadside views.

Working from a small walk up studio on New York’s Third Avenue, Baeder pursued his passion for painting late into the nights, even while continuing to excel at his day job. Always the collector, he began studying vintage postcards of roadside attractions, these augmenting photographs he had himself taken. He frequented postcard dealers, and amassed a large collection of views. The work of itinerant photographers, the postcards were tourist souvenirs. But for Baeder they had a directness, lack of pretension, and unintended artistry.

Baeder in his walk-up NY studio 1972, where gallerist Ivan Karp visited the then unknown artist.

Ivan Karp by Andy Warhol.

New York

In 1972, John Kacere an artist friend of Baeder’s told gallerist Ivan Karp, owner of the OK Harris Gallery about an artist who had created four large “postcard paintings”. Karp, who had been co-director at Leo Castelli Gallery, and had discovered and promoted Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Tom Wesselman, John Chamberlain and others, was curious. He had gone out on his own in 1969, establishing OK Harris Gallery, the second gallery in NY’s Soho district. (It remained influential until Karp's death in 2012 and the gallery's subsequent closing in 2014).

Karp had reviewed the works of thousands of aspiring artists, and was looking for what he called "works of cultural consequence" that possessed "visual power". (Jay Williams)

On February 13, 1972 Karp visited Baeder's studio. Karp was immediately taken by the four canvases depicting post card scenes of a diner, a gas station, a motel, and a tourist camp, and proposed on the spot a September solo show to open the important fall season. This was an unheard-of-offer by Karp for an artist whose work he was viewing for the first time.

Encouraged by Karp's invitation, and fueled by his artistic passion, Baeder quit his lucrative position at McCann- Erickson, at the time New York’s largest advertising agency, and devoted himself full time to painting. This decision was not without personal consequence, it causing the breakup of his marriage, his then wife unsettled by the financial risks and sacrifices inherent in the pursuit of a full-time career in the arts.

Ivan Karp was the first New York dealer to show the work of photorealists, sometimes described as a natural outgrowth of Pop Art.

Baeder accepts “Photorealism” as a convenient description of his work. Indeed, one of his works "John's Diner with John's Chevelle" has been widely used to represent the entire first- and second-generation schools of photorealist artists.

But the description of Baeder as a photorealist only superficially encompasses the breadth of the artist and his accomplishment.

PART II

A Different Kind of Hyperrealist.

Baeder as a young art director in the Mad Men era.

In his brilliant book “John Baeder's Road Well Taken“ (2015), curator and author Jay Williams draws a distinction between Baeder, whose paintings sometimes resembled photographs, and others termed "hyperrealists" such as Richard Estes and Robert Bechtle. From Jay Williams:

“In a 1972 interview, Estes confirmed (Ivan) Karp's assertion that such imagery was conceptual, detached from any involvement with subject, and largely concerned with the challenge of using photographs to inform painting. Once the photograph was shot, "That's the creation of it, almost, and the painting is just the technique of transmitting, or finishing it up, so to speak." Estes went on to explain that the hyperrealists shared "a cold abstract way of looking at things, without any comment or commitment. I think I would tear down most of the places I paint."

From the outset, Baeder's work was markedly different from the others, less focused on the superficial effects of light or rendering complex forms as revealed by the camera, and more concerned with the content of his subject matter—the humanistic implications of roadside architecture. Like the painters who sometimes have been labeled "photorealists," Baeder used photographic images and appreciated their importance. "Matisse said that the invention of the camera was the greatest tool for the painter. I think of the photograph in the way a writer thinks of notes. People who are naive think I take a photograph and paint it. I think of the photograph as a large visual note, and myself back to it on the canvas".

“People who are naive think I take a photograph and paint it.”

… Many of Baeder's photorealist peers were preoccupied with shiny surfaces, reflections in store window, forced perspective, and showy composition. Of the hyperrealists of the early '70's, only Baeder embraced imagery that could be appreciated by everyday people and simultaneously, could be interpreted in terms of human values and archetypal relationships.

An advertising background and humanistic motives place Baeder closer to some earlier artists whom Karp knew well from his years at Castelli Gallery, such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jim Rosenquist. Even though the paintings of these artists bear little resemblance to those of John Baeder, their relationship to photographic images is rarely cool and emotionally neutral. Like Baeder, these painters employed photographic images as "hot" artifacts of human culture with complex symbolic possibilities… Rauschenberg staked out the territory where he, Rosenquist, Baeder, and some other painters found energy and purpose, the down-to-earth region he called "the gap" between art and life. When Rauschenberg used this phrase in the late 1950's, the art world was a small, isolated community—still dominated at that time by Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning—and very much removed from the world of mainstream American culture.

Baeder, always the collector of Americana, posing with restaurant Big Boys.

Baeder's passion for images that reflect genuine human relationships actually may have been fueled by years of advertising work. The anonymous street photographers who created the black-and-white images of downtowns and monochrome postcards of unpretentious tourist cabins and gas stations could never have worked for a modern ad agency. Their photographic works were the polar opposite of the sophisticated, manipulated imagery created by advertising imagery created by advertising professionals in the 1960's and '70'—which only increased their appeal to John Baeder. His interest in photographs of classic small-town culture inevitably led him to the work of the Farm Security Administration photographers of the Roosevelt era. In recent years so much has been written about Walker Evans and his FSA contemporaries that it is difficult to remember that the work of these documentary photographers was drastically undervalued until the late 1960's and '70’s.”

Baeder's sense of flair and style ran in the family: two views of the Baeder cosmetic and perfume factory, Budapest circa1920.

An Experimentalist At Heart.

Baeder has had a remarkable life and an enviable and successful career, his work well represented in major museums and private collections.

His Diner series, as seen in Harry Abram's monographs “DINERS” (1978) and the revised edition (1995), both of which have gone through multiple printings, are especially celebrated.

While Baeder has had numerous museum, and gallery shows, his focus has been broad and eclectic. He has not been afraid to explore new areas, or deviate from a signature look. In addition to his celebrated paintings of diners, his work encompasses: Los Angeles’ taco and food trucks; kitchen windowsill still lifes; diner matchbook covers; and vintage aircraft. He is also a prolific photographer whose color and black and white photos are justly celebrated. He was commissioned by architect Robert Venturi to provide 100 photographs and 16 paintings for the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery landmark exhibit, “Signs of Life, Symbols of the American City.”

For Baeder there is something beyond the object itself, structures incarnating something deep about American and popular culture and the life of the people who patronize and love them. Musicians including Tom Waits and Little Village have enthusiastically used his depictions for album covers, and Baeder's interpretations have entered the visual language as a celebration of a way of life, much of it now vanishing.

One of Baeder's photographic still lifes featuring vintage perfume bottles from the family Budapest archive.

Vincent Scully, Professor of the History of Art at Yale University, identified in his introduction to DINERS a unique aspect in Baeder’s work:

“John Baeder's paintings seem to me to differ from those of his brilliant Magic-Realist contemporaries as they are gentle, lyrical, and deeply in love with their subjects… Baeder is not haunted like Hopper by a sense of something empty, hollow, and solitary in the American experience. Instead, he is youthful, hopeful, a painter-poet who makes us see the beauty of common things—not how funny they are, or how disgusting, or how powerfully expressive even, or how frightening, or just how big—but how lovely, how seen with love… Baeder is entirely at home in his world, and he irradiates it.”

Having become a well-established artist in New York, Baeder visited Nashville on a romantic adventure in 1980. He was charmed by the personality of the town and decided to put down roots. His gentle personality and original vision attracted numerous musicians, songwriters, and publishers as close friends and collectors. And as he became a favorite in his new hometown, he continued to attract the interest of art enthusiasts worldwide.

PART III

Concluding Thoughts

Baeder’s works were represented by Ivan Karp and his OK Harris until Karp’s death in 2012, and the gallery’s closing in 2014. In this period, John's works had entered the Whitney Museum in New York; Cooper-Hewitt Museum, Smithsonian; the Denver Art Museum; Yale University, and many others.

John also had solo exhibitions in London, Paris, Los Angeles, and many other venues. In 2007 Baeder had a major retrospective, organized by the Morris Museum, which brought together dozens of Baeder’s works and drew new attention to an American master.

This tribute to John’s art was a natural for the foremost American museum dedicated to the work of artists born or associated with the American South. Under the leadership of director Kevin Grogan, the Morris’ reputation has grown into an institution far larger than that of a regional museum, approaching the breadth of cultural institutions in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. In addition to its reserves in historical art, the Morris has become known as a patron of the best in contemporary art and music.

Grogan became friends with Baeder during his time as a museum director in Nashville, and at the Morris oversaw the acquisition of John’s iconic painting “Col. Poole’s Pig Hill of Fame” as well as a group of Baeder’s photos and several of his silkscreen prints, adding to the painting “Prout’s Diner”, already part of the collection. The 2007 exhibit, with its accompanying book, Pleasant Journeys And Good Eats Along The Way: The Paintings Of John Baeder was highly popular, making many aware for the first time that this world class painter was living and working in the American South. The exhibit brought record audiences in its travel to several other museums.

Baeder’s work came to additional notice in the publication, in 2014, of his in-depth biography written by Jay Williams, who had curated the 2007 Morris’ show.

I was introduced to John by Kevin Grogan who thought we might hit it off, both of us originally from Atlanta and sharing similar interests, including enthusiasm for the work of Walker Evans and other WPA photographers. I am grateful to Kevin for this introduction, and the meeting of minds which transpired.

After becoming familiar with his art, and having the opportunity to converse with him on many occasions, I told John that I could never look at the most “ordinary” of street scenes as before. He responded modestly, “That is my job. That is the job of the artist”.

Many of Baeder's greatest paintings have long ago been spoken for, and are in major museums and private collections. Still, he has held onto a number of important works, until now unwilling to part with them.

A number of works presented here are illustrated and commented on in one or more of multiple books devoted to Baeder. It is difficult to fathom how a single artist could be so prolific, in addition to authoring seminal books on diners, vintage postcards and street signs. When I asked him about how he managed to do this, he replied simply: “Passion".

Illustrating his ability to focus, Baeder tells a story about the meticulously painted brick walls seen in some of his works. As a boy, he watched stone workers with fascination. In painting years later, he recalled his childhood and thought of himself as a bricklayer, performing and enjoying this task. Similarly, he imagined living the life of those who frequented the diners, and drove the cars depicted, this process giving heart to works which might in a different artist's hands appear flat and lifeless.

During his years in New York, Baeder was introduced to the writings and works of Carl Jung. Baeder had never seen his Diners as mere “surface”, always intensely focused on the life and hearts of the people who frequented these community hearths. His Jungian studies opened up additional perspective.

At the time of his first exhibit in Atlanta (1964), Baeder stated that his foremost aim was to be a realized being, not an artist. He has also expressed that his role was not just to create beautiful canvases, but to preserve for future generations something of a life they might not otherwise know.

From John Baeder’s collection of street signs.

But as Kevin Grogan observes, while Baeder is a passionate preservationist, he was never motivated by nostalgia. His work “mysterious and evocative” often has as its principal concern not the “faded structures he depicts but the lives of those who built and used them”.

By memorializing diners, gas stations, motels, roadside attractions and other structures, he reflects back to us their importance in our collective memory and consciousness. With their welcoming horizontality and acceptance of all, diners came to represent for Baeder an archetypal feminine energy. Like a person chasing the last rays of the sunset, Baeder has been on a lifelong quest to document and interpret the American spirit as seen in our everyday life.

I believe it is impossible to immerse oneself in Baeder’s work and ever again view our world in the same way.

I am exceedingly pleased and honored to be able to make available to you these rare works from John’s private collection, this in collaboration with ACA Galleries in New York.